Turns out, you lie to yourself all the time. Don’t worry, it’s completely natural – an evolutionary fail safe installed in our brains since consciousness evolved. However, these lies are rarely in your best interest. Developing the discipline to identify these lies is key in life and in business.

Great growth can come from reflecting and thinking about how we think. We mention this often in our

posts, and especially when we talk about tapping into your

Wise Advocate and moving from Low Ground to High Ground thinking. Your Wise Advocate is that inner voice that can provide guidance and insight when you need it most. By focusing on mental activities that are more reflective in nature, you’ll start to notice that both controlling your inner monologue and seeking your best true self is possible. These activities can help give you third-person insight into your first-person experience.

The lasting legacies of philosopher René Descartes are many, but one of his most studied are his theories of

mind-body distinction, or dualism. His argument that the nature of the mind is completely different from that of the body gave rise to the now famous dilemma regarding mind-body causal interaction. Descartes’ questions about the mind and its influence on our actions remains as heavily debated today as when he introduced them. We can look at this dualism as a mind (intellectual) and brain (physical) distinction.

Mind/Brain Identify theory argues that the states and processes of the mind are identical to the states and processes of the brain. To them, the mind simply does not exist as a separate entity.

Jeffrey Schwartz, author of the best seller

You are Not Your Brain, is part of the other camp — one that believes that the mind is intimately connected with, and can exert powerful effects on, the brain. We support this distinction. In short, we believe that people are so much more than what their brain is trying to tell them they are, and that the brain often gets in the way of our true, long-term

goals and values in life (i.e., our true self). The brain gets it wrong because the mind is an unreliable narrator – simply the mind sends deceptive messages.

The idea of the unreliable narrator has been around for as long as we’ve been expressing thoughts and turning them into stories. One of the oldest examples of the use of the unreliable narrator is the comedic play, “The Frog” published by Aristophanes in 405 BC. Later, the 1920 film, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” would use the idea of the unreliable narrator to deliver the surprise twist wherein the main character is revealed to have been in a mental institution the whole time.

Unreliable narrators in fiction are usually assigned different classic characteristics that compromise their credibility and fuel their unreliability. Even though these characteristics are most often applied to fictional characters, these traits are just as easily assigned to different types of thoughts. These four categories include:

Picaro – The character known for exaggerating.

Madman – The character who is mentally detached from reality. An extreme example would be Patrick Bateman in the Brett Easton Ellis novel “American Psycho.”

Naif – The character whose narrative abilities are impacted by inexperience or age like Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye.”

Liar – The character who fabricates stories, often to achieve a desired outcome or make themselves look better.

So, what is unreliable narration in the real world? It shows up in two ways, one from self-defeating thoughts and the second is the way we process information.

First, when we become aware of how we process and consider our own thinking, we’re able to recognize that we are constantly bombarded with self-defeating thoughts. It’s the nature of the human condition to focus on the negative versus the positive. When things are going well we tend not to think too deeply about them, and when we’re really good at something we don’t necessarily question it.

This means we tend to operate with a bias for the negative and focus on what’s not working. We allow ourselves to be filled with self-defeating thoughts that don’t represent our best selves. Our own faulty thinking can cause us to fall into one or more of the following thought traps

highlighted in Jeffrey Schwartz’s work —

- All or nothing thinking. Taking a black and white perspective that relies on the assumption that things are either perfect or terrible. Example: The meeting didn’t go perfectly so it was a complete failure.

- Catastrophizing. This type of thinking revolves around the expectation that something bad is always about to happen.

- Discounting the Positive. Undervaluing positive qualities about yourself and choosing to focus only on what you’re doing wrong.

- Emotional Reasoning. This type of response deals directly with the same issues of an unreliable narrator. Criticizing yourself because you’re having an uncomfortable response and self-defeating thoughts.

- Mind Reading. This type of thinking is dangerous because it revolves around assuming that you know what another person is thinking. Example: Telling someone hello and if they don’t respond, assuming it is because they’re upset with you.

- “Should” Statements. Setting up false expectations for yourself and others based on “should” and “ought to” type statements. This type of thinking often leads to resentment and frustration.

- Faulty Comparisons. These comparisons set you up for failure and rely on positioning yourself against others in a way that disregards the positive.

- False Expectations. Letting your desire for a certain outcome impact the way you comprehend and process what happened.

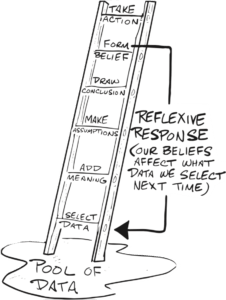

In addition to this negative self-talk, we also operate as if our assumptions, conclusions and beliefs are data. Any of us can look at an event — something happens in the world and our brain processes it. There’s an automaticity to it, where we can quickly go from seeing somebody having a physical response (furrowed brow) to deciding they must be worried. From this assumption we can quickly create a narrative that makes sense.

This is where our unreliable narrator and the

Ladder of Inference come together. We are inferential beings and the speed at

which we make inferences causes our minds to become unreliable narrators. At the bottom of the ladder we have facts and from there we experience reality based on beliefs and prior experience. We apply our existing assumptions, draw conclusions and develop our belief systems that then inform our actions.

All of this, from mind-body dualism to faulty thinking, brings us back to the decade’s

hottest wellness trend touted by everyone from Oprah to Marc Benioff — mindfulness. What the mindfulness movement gets right is the emphasis on becoming aware of automatic reactions. It is a tool of self-discipline that asks us to consider reframing our initial thoughts.

It’s about recognizing that our thoughts and assumptions may not necessarily be the truth. The ability to process the data as we receive it before jumping to conclusions informed by our individual experiences would undoubtedly make us better, more capable people.

Incredibly, we all have the ability to do exactly that through the evolutionary gift of neuroplasticity. Through changes in our neural pathways and synapses in response to factors like behavior and environment, we are able to rewire our brains. By deleting neural connections that no longer serve us and strengthening the ones that do, we can start to send different connections that change our thinking.

The point is — we are not simply our brains or the thoughts we have. We are so much more than that. Understanding and accepting that your brain is an unreliable narrator is just one tool in your intellectual toolbox. We are all constantly learning and evolving as we respond to different actions and situations. Who we are isn’t determined by what we think, it’s by the actions we take – hopefully informed by our Wise Advocate.

Turns out, you lie to yourself all the time. Don’t worry, it’s completely natural – an evolutionary fail safe installed in our brains since consciousness evolved. However, these lies are rarely in your best interest. Developing the discipline to identify these lies is key in life and in business.

Great growth can come from reflecting and thinking about how we think. We mention this often in our posts, and especially when we talk about tapping into your Wise Advocate and moving from Low Ground to High Ground thinking. Your Wise Advocate is that inner voice that can provide guidance and insight when you need it most. By focusing on mental activities that are more reflective in nature, you’ll start to notice that both controlling your inner monologue and seeking your best true self is possible. These activities can help give you third-person insight into your first-person experience.

The lasting legacies of philosopher René Descartes are many, but one of his most studied are his theories of mind-body distinction, or dualism. His argument that the nature of the mind is completely different from that of the body gave rise to the now famous dilemma regarding mind-body causal interaction. Descartes’ questions about the mind and its influence on our actions remains as heavily debated today as when he introduced them. We can look at this dualism as a mind (intellectual) and brain (physical) distinction.

Mind/Brain Identify theory argues that the states and processes of the mind are identical to the states and processes of the brain. To them, the mind simply does not exist as a separate entity.

Jeffrey Schwartz, author of the best seller You are Not Your Brain, is part of the other camp — one that believes that the mind is intimately connected with, and can exert powerful effects on, the brain. We support this distinction. In short, we believe that people are so much more than what their brain is trying to tell them they are, and that the brain often gets in the way of our true, long-term goals and values in life (i.e., our true self). The brain gets it wrong because the mind is an unreliable narrator – simply the mind sends deceptive messages.

The idea of the unreliable narrator has been around for as long as we’ve been expressing thoughts and turning them into stories. One of the oldest examples of the use of the unreliable narrator is the comedic play, “The Frog” published by Aristophanes in 405 BC. Later, the 1920 film, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” would use the idea of the unreliable narrator to deliver the surprise twist wherein the main character is revealed to have been in a mental institution the whole time.

Unreliable narrators in fiction are usually assigned different classic characteristics that compromise their credibility and fuel their unreliability. Even though these characteristics are most often applied to fictional characters, these traits are just as easily assigned to different types of thoughts. These four categories include:

Picaro – The character known for exaggerating.

Madman – The character who is mentally detached from reality. An extreme example would be Patrick Bateman in the Brett Easton Ellis novel “American Psycho.”

Naif – The character whose narrative abilities are impacted by inexperience or age like Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye.”

Liar – The character who fabricates stories, often to achieve a desired outcome or make themselves look better.

So, what is unreliable narration in the real world? It shows up in two ways, one from self-defeating thoughts and the second is the way we process information.

First, when we become aware of how we process and consider our own thinking, we’re able to recognize that we are constantly bombarded with self-defeating thoughts. It’s the nature of the human condition to focus on the negative versus the positive. When things are going well we tend not to think too deeply about them, and when we’re really good at something we don’t necessarily question it.

This means we tend to operate with a bias for the negative and focus on what’s not working. We allow ourselves to be filled with self-defeating thoughts that don’t represent our best selves. Our own faulty thinking can cause us to fall into one or more of the following thought traps highlighted in Jeffrey Schwartz’s work —

Turns out, you lie to yourself all the time. Don’t worry, it’s completely natural – an evolutionary fail safe installed in our brains since consciousness evolved. However, these lies are rarely in your best interest. Developing the discipline to identify these lies is key in life and in business.

Great growth can come from reflecting and thinking about how we think. We mention this often in our posts, and especially when we talk about tapping into your Wise Advocate and moving from Low Ground to High Ground thinking. Your Wise Advocate is that inner voice that can provide guidance and insight when you need it most. By focusing on mental activities that are more reflective in nature, you’ll start to notice that both controlling your inner monologue and seeking your best true self is possible. These activities can help give you third-person insight into your first-person experience.

The lasting legacies of philosopher René Descartes are many, but one of his most studied are his theories of mind-body distinction, or dualism. His argument that the nature of the mind is completely different from that of the body gave rise to the now famous dilemma regarding mind-body causal interaction. Descartes’ questions about the mind and its influence on our actions remains as heavily debated today as when he introduced them. We can look at this dualism as a mind (intellectual) and brain (physical) distinction.

Mind/Brain Identify theory argues that the states and processes of the mind are identical to the states and processes of the brain. To them, the mind simply does not exist as a separate entity.

Jeffrey Schwartz, author of the best seller You are Not Your Brain, is part of the other camp — one that believes that the mind is intimately connected with, and can exert powerful effects on, the brain. We support this distinction. In short, we believe that people are so much more than what their brain is trying to tell them they are, and that the brain often gets in the way of our true, long-term goals and values in life (i.e., our true self). The brain gets it wrong because the mind is an unreliable narrator – simply the mind sends deceptive messages.

The idea of the unreliable narrator has been around for as long as we’ve been expressing thoughts and turning them into stories. One of the oldest examples of the use of the unreliable narrator is the comedic play, “The Frog” published by Aristophanes in 405 BC. Later, the 1920 film, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” would use the idea of the unreliable narrator to deliver the surprise twist wherein the main character is revealed to have been in a mental institution the whole time.

Unreliable narrators in fiction are usually assigned different classic characteristics that compromise their credibility and fuel their unreliability. Even though these characteristics are most often applied to fictional characters, these traits are just as easily assigned to different types of thoughts. These four categories include:

Picaro – The character known for exaggerating.

Madman – The character who is mentally detached from reality. An extreme example would be Patrick Bateman in the Brett Easton Ellis novel “American Psycho.”

Naif – The character whose narrative abilities are impacted by inexperience or age like Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye.”

Liar – The character who fabricates stories, often to achieve a desired outcome or make themselves look better.

So, what is unreliable narration in the real world? It shows up in two ways, one from self-defeating thoughts and the second is the way we process information.

First, when we become aware of how we process and consider our own thinking, we’re able to recognize that we are constantly bombarded with self-defeating thoughts. It’s the nature of the human condition to focus on the negative versus the positive. When things are going well we tend not to think too deeply about them, and when we’re really good at something we don’t necessarily question it.

This means we tend to operate with a bias for the negative and focus on what’s not working. We allow ourselves to be filled with self-defeating thoughts that don’t represent our best selves. Our own faulty thinking can cause us to fall into one or more of the following thought traps highlighted in Jeffrey Schwartz’s work —

which we make inferences causes our minds to become unreliable narrators. At the bottom of the ladder we have facts and from there we experience reality based on beliefs and prior experience. We apply our existing assumptions, draw conclusions and develop our belief systems that then inform our actions.

All of this, from mind-body dualism to faulty thinking, brings us back to the decade’s hottest wellness trend touted by everyone from Oprah to Marc Benioff — mindfulness. What the mindfulness movement gets right is the emphasis on becoming aware of automatic reactions. It is a tool of self-discipline that asks us to consider reframing our initial thoughts.

It’s about recognizing that our thoughts and assumptions may not necessarily be the truth. The ability to process the data as we receive it before jumping to conclusions informed by our individual experiences would undoubtedly make us better, more capable people.

Incredibly, we all have the ability to do exactly that through the evolutionary gift of neuroplasticity. Through changes in our neural pathways and synapses in response to factors like behavior and environment, we are able to rewire our brains. By deleting neural connections that no longer serve us and strengthening the ones that do, we can start to send different connections that change our thinking.

The point is — we are not simply our brains or the thoughts we have. We are so much more than that. Understanding and accepting that your brain is an unreliable narrator is just one tool in your intellectual toolbox. We are all constantly learning and evolving as we respond to different actions and situations. Who we are isn’t determined by what we think, it’s by the actions we take – hopefully informed by our Wise Advocate.

which we make inferences causes our minds to become unreliable narrators. At the bottom of the ladder we have facts and from there we experience reality based on beliefs and prior experience. We apply our existing assumptions, draw conclusions and develop our belief systems that then inform our actions.

All of this, from mind-body dualism to faulty thinking, brings us back to the decade’s hottest wellness trend touted by everyone from Oprah to Marc Benioff — mindfulness. What the mindfulness movement gets right is the emphasis on becoming aware of automatic reactions. It is a tool of self-discipline that asks us to consider reframing our initial thoughts.

It’s about recognizing that our thoughts and assumptions may not necessarily be the truth. The ability to process the data as we receive it before jumping to conclusions informed by our individual experiences would undoubtedly make us better, more capable people.

Incredibly, we all have the ability to do exactly that through the evolutionary gift of neuroplasticity. Through changes in our neural pathways and synapses in response to factors like behavior and environment, we are able to rewire our brains. By deleting neural connections that no longer serve us and strengthening the ones that do, we can start to send different connections that change our thinking.

The point is — we are not simply our brains or the thoughts we have. We are so much more than that. Understanding and accepting that your brain is an unreliable narrator is just one tool in your intellectual toolbox. We are all constantly learning and evolving as we respond to different actions and situations. Who we are isn’t determined by what we think, it’s by the actions we take – hopefully informed by our Wise Advocate.