Trying to be a better performance coach for your team? This article discusses a few insights into being more effective.

One of my favorite leadership books is First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently (1999) by Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman. They make the case that great managers “spend the most time with their most productive employees.”

This idea was, and arguably still is, revolutionary for most performance coaches and managers. Managers routinely admit to spending the most time with their lower performers yet paradoxically acknowledge that success will mostly be driven by medium to high performers. Why is this?

2 Reasons Managers Make This Mistake

Their reasoning for this behavior typically falls into two buckets. The first bucket is that the “system” may require the manager to invest in a performance improvement plan (PIP). This requirement can take both time and energy, and besides, the middle to high performers seem to be happy and doing well.

Many managers admit to having little success in improving lower performers with the use of a PIP. There are various theories on the lack of success in improving low performers ranging from the question about fit to the Golem effect – where the manager starts a cycle of pressure and supervision that paradoxically leads to lower performance. The Golem effect works like this: a manager may come to believe that a direct report lacks skill or will. The belief sets in motion a PIP that:

- Sets more explicit targets and deadlines

- Assigns more routine tasks

- Monitors the employee on a regular basis

- Emphasizes operational concerns instead of strategic ones

- Is overly paternalistic in tone and thought

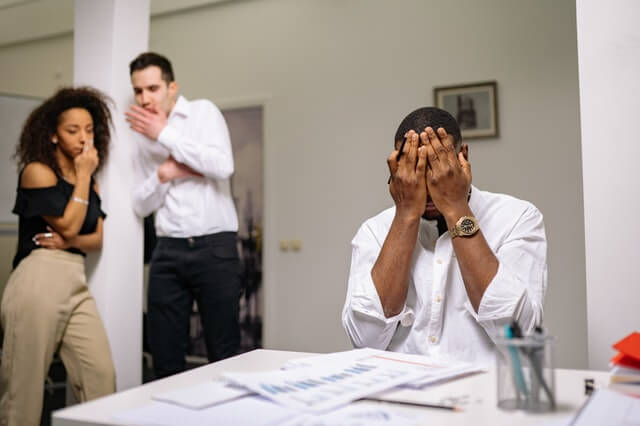

The impact of the manager’s behavior makes it obvious to their direct report that there is little trust in their ability. The manager’s beliefs lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy as the direct report loses motivation and becomes less likely to achieve.

The second bucket is our focus here. Many managers see their role as improving the performance of the team: they want to be effective performance coaches to help everyone succeed. Clearly, the “flashing red light” is that lower performers appear ready-made to fulfill this role. The reality is that the lower performer will often find themselves in situations that grab the manager’s attention. We are all wired for negativity and our attention is quickly drawn to what is not working. It is easy to view lower performers as problems to be solved.

Conversely, we are told (or tell ourselves) that higher performers don’t often require or even want the coaching. Where it gets really interesting is that when we ask managers why a high performer would not want their coaching the answer falls along the lines of, “They say that they are good and are being successful.” Perhaps Buckingham and Coffman have it all wrong – you can’t coach people who don’t want to be coached. But this begs the question, why don’t the higher performers want your coaching?

High Performers Need a Better Performance Coach

What managers fail to recognize is the possibility that the higher performers don’t want the manager’s coaching because they have concluded that the coaching, well, stinks. How would they know it stinks if they are not being coached? Well, they see all of the wonderful work the manager is doing with the lower performers, and they have decided to pass.

Coaching lower performers is arguably an easier skill lift. You diagnose what they are doing wrong, you get to “tell” them what to do, and then you can manage them against their deliverables. I understand the objection to this point of view – some say all coaching should be ask-driven. I would argue that back in the real world if you have someone underperforming, a lot of direction is inevitable. Let’s not forget the brain chemistry payoff of being the one with the answers.

The gap between low performer coaching and high performer coaching is significant.

Coaching higher performers requires nuance. It requires humility, vulnerability, asking good questions, listening, and, ultimately, not having the answer. For twelve years we have asked managers: What do you have to believe about someone in order to coach them?

The answers are all around skill (the coachee has skill/knowledge/capability) and will (they are motivated, coachable). What everyone misses is what is arguably the most important for this level – that the coachee has insight that the performance coach does not have. It is this underlying belief that you are not all-knowing that makes it a conversation and ensures your questions are driven by curiosity.

Getting better at coaching mid to high performers should be an imperative. It is worth the effort because it is in this population that your success and the success of your organization reside.